“The Riff Song.” Words by Otto Harbach, Oscar Hammerstein 2nd, and Frank Mandel, with music by Sigmund Romberg. Recorded in London in February 1927 by Ronnie Munro and His Dance Orchestra, with vocals by Maurice Elwin. Ariel 4251 (from Parlophone E-5762) mx. E-1206-1.

Personnel: Ronnie Munro-p dir. Jack Jackson-Max Goldberg-Frank Wilson-Lloyd Shakespeare-t / Lew Davis-tb / Charlie Swinnerton-Ben Davis-?Nat Star-cl-as / Buddy Featherstonhaugh-cl-ts / vn / Barry Mills or Carrol Gibbons-2nd p / Len Shevill-bj-g / bb-sb / Max Bacon-d-vib / Wag Abbey-Rudy Starita-d-x / Maurice Elwin-v

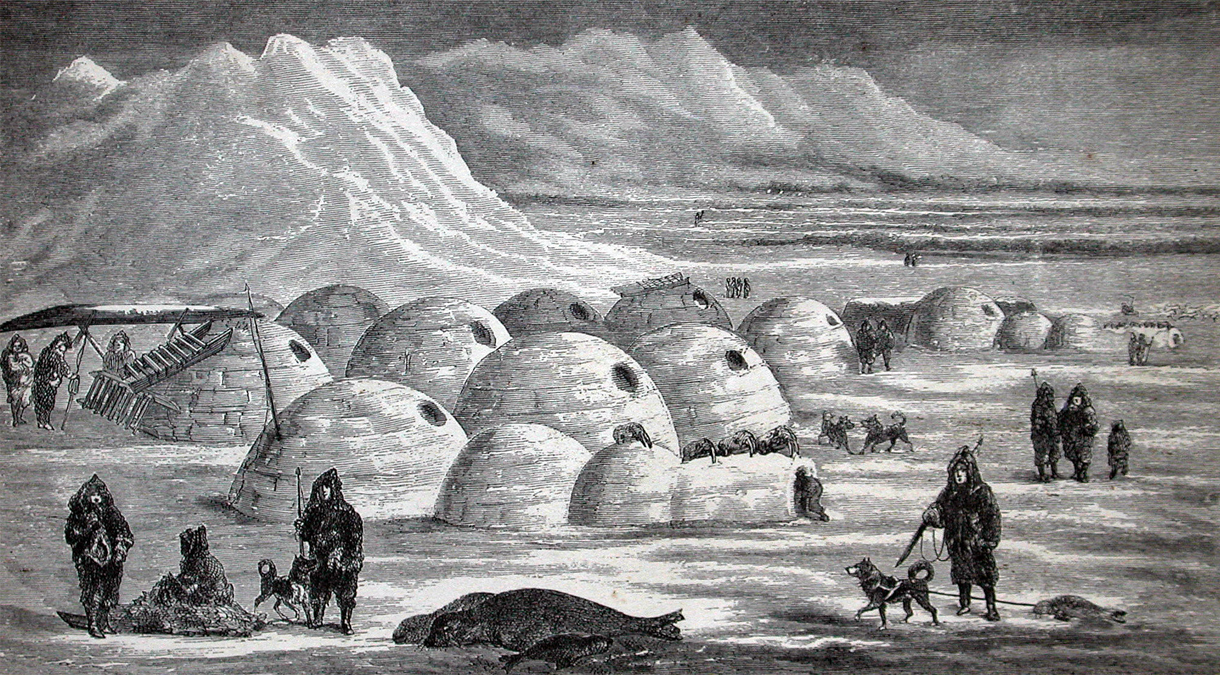

From 1921 to 1926, Moroccan Berber insurgents known as Riffians (named for the mountainous Rif region) rebelled against the colonizing forces of Spain. The Riffians proved to be formidable and skilled opponents, in spite of the asymmetry of the warfare (with the Spanish using aircraft and even chemical weapons). It was only with the intervention in 1924 of France (which had its own protectorate in Morocco), aided by American mercenary aviators, that the Berbers began to falter. In 1926 they were forced to surrender.

Meanwhile, in America (which was trying to remain neutral), Hungarian-born composer Sigmund Romberg and his team of lyricists (Harbach, Hammerstein, and Mandel) seem to have gauged that popular revulsion at the involvement of the American mercenaries in what was perceived as an unfair conflict, as well as a growing vogue for all things Saharan, would create an enthusiastic audience for an operetta sympathizing with the Riffians. The Desert Song had a convoluted plot involving a masked white savior character named Pierre, who, while posing as a Berber and leading the Riffians against the French, is actually himself French and even the son of the French general opposing the Berbers. As the rebel leader “the Red Shadow,” Pierre leads a double life comparable to those of the Scarlet Pimpernel and Zorro (a more recent parallel would be Superman/Clark Kent). Early in the drama, he sings “The Riff Song,” in which he boasts of the valor and prowess of “the Riffs” (i.e., the Riffians) and the Red Shadow.

Ronnie Munro’s arrangement of the song is similar to the one that American Don Voorhees had used the previous year and includes a few (possibly not very authentic) gestures in the direction of world music that nevertheless serve to summon a feeling of place. Maurice Elwin is given just one brief iteration of the chorus to sing, but it stands out as a particularly impressive vocal performance. Elwin had had his formal education at the Royal Academy of Music, where operatic technique would have been a mainstay of instruction. It is pleasing to hear him applying his training judiciously in the context of operetta.

“The Riff Song” was recorded in America in 1926 by Nat Shilkret and the Victor Orchestra (v. The Revelers) and by Don Voorhees and His Earl Carroll Vanities Orchestra (v. The Shannon Quartet). In 1927, British artists who recorded “The Riff Song” include Alfredo’s Band, the Savoy Orpheans (dir. Carroll Gibbons), Jack Payne and His Hotel Cecil Orchestra (v. orchestra), the Debroy Somers Band (in a Desert Song medley), Harry Bidgood’s Orchestra (on Aco and Coliseum with vocalist John Thorne and on Broadcast with Bobby Sanders), Stan Greening’s New Regenta Orchestra (in a Desert Song medley), and Bert Firman’s Dance Orchestra (as Eugene Brockman’s Dance Orchestra).